Dear Readers,

During the month of May I will be sending you a 4-part excerpt from Chapter 1 of Sacred Selfishness, Captives of Normalcy.

Awakening to Our Stories

To understand what Jung meant by a religious attitude in the second half of life, and what this attitude has to do with our emotional problems, we need to become more familiar with what he calls the individuation process, his model for how our personalities grow. While each of us grows and ages physically, whether we like it or not, the same fact isn’t true about our psychological growth. The individuation process recognizes that after we have grown to a certain point psychologically, we have to make an effort; we have to pursue self-knowledge, to mature as people and live in a satisfying manner in our relationships and culture.

When we talk about the way we attain individuation, we are really talking about how we discover and participate in the stories we are creating with our lives. Every life in retrospect is a story and, like a story, has a beginning, unfolding events, and an end. In a narrative the story is concerned with individuals, how they feel and how people feel about them, rather than what they do or what is done to them. As I presented myself as a young man in the introduction of this book, I quickly became a character in a story and you automatically began to wonder where this story was leading. Stories become absorbing. So do our lives when we begin to look at them this way. They become stories when we are fully engaged in living them and begin to reflect on that experience.

Every life is full of tragedy and comedy, stops and starts, shaky beginnings, wanderings, wrong turns, and changes of direction. Frequently our years are marked by difficult loves, unfulfilled dreams and challenges, laughter, tears, separations, and reunions. Behind many of these events lie causes both within and outside of ourselves. For example, how our parents influenced us for better or worse and how we continue to live out our early conditioning affects our relationships today.

It may be helpful to look at some insights into stories offered by the novelist E. M. Forster. In his book Aspects of the Novel, he explains the difference between a simple story and a narrative that leads to meaning. In the latter we ask why to events. For example, “The king died and then the queen died” is a simple story. But if I say, “The king died and then the queen died of grief,” we have a plot, a pattern that unfolds a deeper meaning within the sequence of events that happened as they did. As an analyst I would say that an unexamined life is, to a large extent, a simple story, while an examined life becomes a narrative that can lead us to understand a sense of purpose and completion in our lives and a feeling of satisfaction as we are living through them.

The process of individuation follows a pattern that gives every life a unique expression of meaning; I will discuss that pattern later in this book. Learning how to get in touch with the stories we are creating allows us to participate consciously in their development. We do this by reflecting on our lives, seeking insight into their events, and trying to understand how our feelings, bodies, and unconscious minds are participating in and responding to our stories. We will see some helpful techniques in this regard in part 2. But for now what’s important to think about is this: that developing knowledge about our whole selves, expanding and deepening our self-awareness, is a key to learning about our individuation processes. And just as our stories go from beginning to end, our individuation, our psychological growth, must do the same.

By pursuing individuation with deliberation and honesty, Jung believed we could perceive the pattern or plot of the stories we are living and through this perception arrive at an understanding of a place of grace or true center in our personalities that he termed the “Self.” The Self includes the unique pattern, the potential person, who is within each of us and seeks throughout a lifetime to be recognized and expressed through our conscious personalities and their actions. Therefore the Self includes our conscious and unconscious minds and our potentials.

The basic outcome of this complicated process is a growth in consciousness. As we come to know ourselves more fully and become more alert to the aspects of our stories, in the past and present, we are naturally increasing our capacities for expressing the potential people we are meant to be. Simply put, the better we know ourselves the more personal and pure our actions become because they aren’t hidden, curtailed, or contaminated by the forces that shaped our early lives. Authentic actions disclose who we are to other people. Without self-knowledge our behaviors basically reflect needs common to everyone or the training and wounds of our childhoods. I recall being visited by a young college professor who told me with considerable anger that he was in trouble with his department chairman and the dean. He felt they didn’t understand what a creative teacher he was.

“They make me feel stupid,” he said, “like an adolescent.” Pausing, he then continued, “Like my father did.”

And as you may imagine his friends were the other “misunderstood” rebels on the faculty who actually invited most of the trouble they were in. In another situation a woman who consulted with me had an angry, belittling father and found she would freeze when someone raised his or her voice. By learning to understand ourselves better we can discover the negative effects of our histories, work to change them, build on our strengths and potentials, and relate to people and events in a more straightforward, authentic manner. Every time we take a step toward becoming aware of and transforming one of these past influences, we become less of a prisoner of the forces in our histories and assure that our future actions will express more of who we really are.

Generally, it doesn’t take much reflection to realize that most of us haven’t gotten out from under the early influences in our lives nearly as much as we like to think we have. It’s difficult to fully separate or individuate from our families or from institutional and cultural influences, and for good reason. They affect us before our identities are secure; we actually use them for models; their values are the initial foundation of our values; they have power and we don’t; and we’re trained to make decisions and behave in a manner that meets their approval. We’re taught to “color within the lines” or “pay attention,” and trained to “hide our feelings.” We’re silenced with injunctions like, “Don’t you dare talk back.” Brushed off with comments like “Don’t bother me I’m busy,” and taught to be passive by being told to “turn the other cheek.” “Forgive seventy times seven.” “Honor your father and mother.” In a similar vein we hear, “You’re not living up to your potential”; “Men are strong”; “Women aren’t good at math”—and other countless messages reflecting family and cultural influences that are structured into our personalities while we are too young to evaluate them. I remember a young woman, a physician with two children, who still felt compelled to scrub out the bathrooms the way her mother did. “The cleaning woman just never gets it done right,” she would explain. In another situation a man forty years old and president of his own company couldn’t tell his wife what he really wanted from her. “I think she’d actually prefer it if I did,” he reported, “but every time I try to I remember how many times my mother told me to be gentle and thoughtful to women, not demanding like my father.”

The expectations and values we grow up with are insidious, and even the negative ones are often seductive. How many of us try to chase away our restless dissatisfaction, despite our nice homes, jobs, and families, by asking ourselves, What have I got to complain about? How can I complain when so many other people are less fortunate? And, our ability to face dissatisfactions is complicated even further if we have reached a level of education and success beyond that of our families of origin. It’s very scary for us to outgrow our families psychologically, and realizing we are doing so may leave us feeling terribly guilty and even ashamed of ourselves. It can also leave us feeling like exiles, without a home or roots or people who care about us and understand us on a basic level.

I remember a thirty-one-year-old woman who told me, “I’ve just felt horrible about my parents since my wedding.” She had been raised in a small southern town where her parents had been good but ordinary people. Once she was out of high school she moved to a large city, worked her way through college, and after a few years in the business world became a buyer in a well-known department store. When she was twenty-nine, she married a magazine writer in a small, lovely church in the city. During the rehearsal dinner, the service, and the reception she noticed her parents were uncomfortable and didn’t fit in with her friends and colleagues. She said, “I could see the distress in their eyes. They didn’t feel at home with our friends and they acted like I was someone they hardly knew. I feel so ashamed because I love them but I don’t even want to go see them.”

She isn’t an isolated case. Conway had become a gifted minister and was embarrassed by his mother’s loud, opinionated way of dominating a conversation. And Karen, a popular young woman who acted as the hostess in the restaurant she and her husband owned, was terrified of being around her parents. Their ethnic prejudices, which they made no effort to hide, embarrassed her in front of her husband, in-laws, and friends and made her want to keep her children away from their grandparents. Duncan had even stronger feelings. He came from a violent, abusive family and after years of therapy is doing well while his brother and sister continue to struggle with mental illness and addictions. Duncan says he has “survivor’s guilt” and is in conflict with a society that bombards him with sentimental advertisements on Mother’s Day and Father’s Day while he despises his parents.

In another situation a friend of mine got stuck in a pattern of conflict with his parents that lasted for decades. He is a person I have always admired as having a truly brilliant mind. It was easy for him to excel in his classes and later win scholarships to universities and graduate schools that were beyond his parents’ dreams. But early in his life he began to feel that his parents were expecting more and more from him and were using his performance to bolster their own self-esteem and social status. The more they expected of him without trying to find out who he really was, the more he resented the pressure he felt from them. As a result he has spent a lifetime being a magnificent failure––making lots of money and losing it, having a lovely family and turning it into a disaster, pleasing and destroying, living in a cycle of success and defeat that carries on his early conflicts. It is easy, much too easy, to remain trapped in the expectations and values of our parents and follow the highways approved by our society, or to live our lives in rebellion against them, stuck in the swamps with other people trapped by their resentments. Yet, nature intends us to be more than the simple tales we’ve developed out of adaptation, fear, and compensation. We are attracted to becoming more conscious and we also fear it, because it means a journey out of our past illusions into personal responsibility for ourselves.

All of this complex psychological language is, of course, only a tool to help us examine our lives and find that “story.” Our stories must be unraveled from our tangled personal histories and the pressures of our lives—and then lived as fully as possible. The individuation process guides us in living our stories with meaning, a sense of honesty and destiny that is unique and our own, while remaining part of life’s greater story.

If we stop and think about this process it will make sense. We feel more secure once we realize that it isn’t necessary to struggle to be like someone else or meet another’s ideals. As we feel more complete, at home within ourselves, free to explore our creative abilities, developing our strength and authority, it becomes natural to seek the ways we resemble the human “family,” and how we can relate, belong, and contribute without again losing ourselves.

It is our lot, the Jungian author Robert Johnson tells us, to live through the dualities and conflicts in our inner and outer lives until we become conscious of the underlying unity within us that is the source out of which our complexity and vitality flows. The Self is a metaphor for this unity. Whether we want to follow our mind or our heart, or are stuck between them, they both have the same source.

However you look at us—body, mind, spirit, conscious, and unconscious are all parts of the same whole. The Self is a kaleidoscope that recognizes all the aspects of our being and all the potentials within us that may develop and emerge into a unique pattern of life. The unity experienced by an illuminated person, one who has lived and attained a level of consciousness above the ordinary, is often thought of as a knowledge of the soul, of the image of God, the divine or transcendent within each human life. The path toward the Self, the individuation process, goes hand in hand with the development of consciousness.

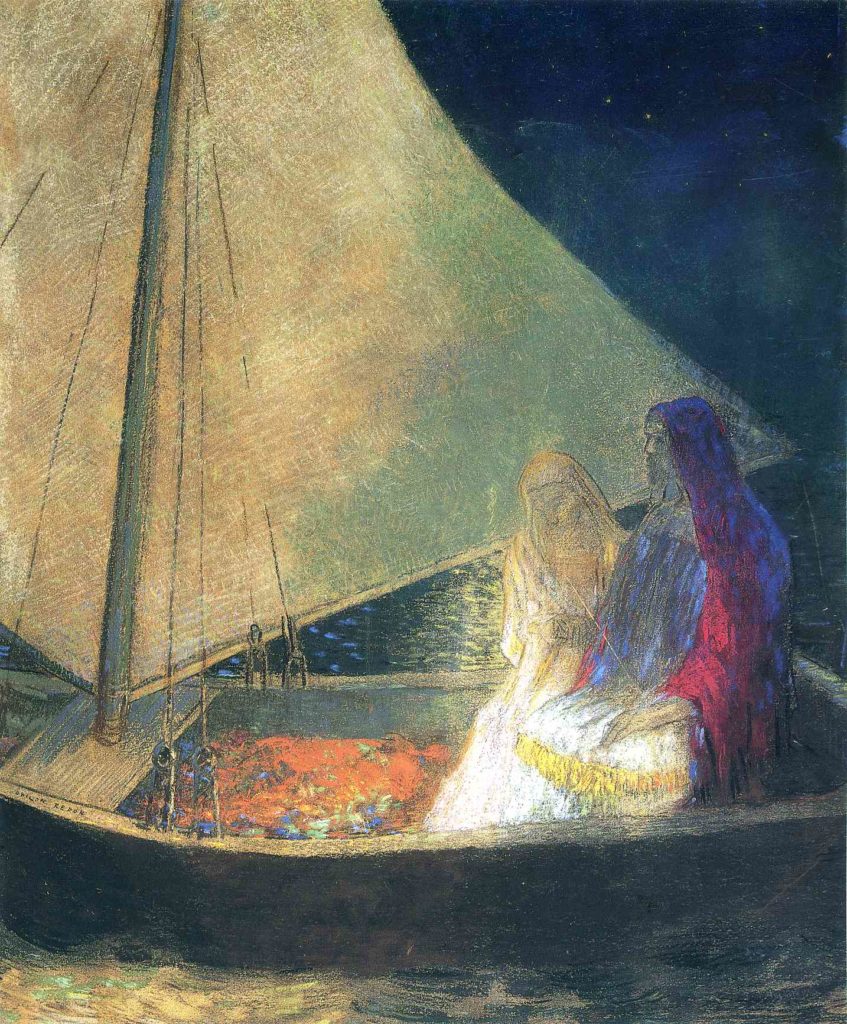

art credit: Boat with Two Figures, Odilon Redding

Book Excerpts and Resources

, authenticity, creative life, healthy personality, Individuation, Jung, Jungian psychology, living authentically, Sacred Selfishness, self-acceptance, self-judgement, self-loving

Please stay positive in your comments. If your comment is rude it will get deleted. If it is critical please make it constructive. If you are constantly negative or a general ass, troll or baiter you will get banned. The definition of terms is left solely up to us.

Leave a Reply